What Material Does Dan Flavin Use to Make Art?

Introduction

One might non think of calorie-free as a affair of fact, but I exercise. And information technology is, every bit I said, as plain and open and direct an fine art as you volition always find.

—Dan Flavin, 1987

For more than three decades, Dan Flavin (1933-1996) vigorously pursued the artistic possibilities of fluorescent light. The creative person radically limited his materials to commercially available fluorescent tubing in standard sizes, shapes, and colors, extracting banal hardware from its commonsensical context and inserting information technology into the globe of loftier fine art. The resulting body of work at once possesses a straightforward simplicity and a deep composure.

Dan Flavin, untitled (in honor of Harold Joachim) 3, 1977, pink, xanthous, bluish, and greenish fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) foursquare beyond a corner, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

1 of 16

Youth and Educational activity

Flavin was built-in in Queens, New York, in 1933, where he went to parochial schoolhouse, before attending (against his wishes) a preparatory schoolhouse for the seminary in Brooklyn. In 1953, he enlisted in the Air Force and trained as a meteorological technician. Although Flavin sketched and drew from an early age, it was at this time, while working as a meteorological adjutant, that he began to spend most of his free fourth dimension making art, visiting museums in Washington, D.C., and New York, and collecting art. In the belatedly 1950s, the young Flavin attended Columbia Academy and studied the history of art, while working a series of jobs that included mailroom clerk at the Guggenheim Museum and guard at the Museum of Mod Art, and, later, the American Museum of Natural History. During this period, Flavin fabricated important art earth contacts and produced mixed media collages that included constitute objects from the streets, especially crushed cans.

Dan Flavin, Juan Gris in Paris (adieu Picabia), 1960-1962, crushed can, oil on Masonite, and acrylic on balsa, xix 7/8 x 24 10 3 3/16 in., Collection Stephen Flavin, Photograph: Bill Jacobson, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

ii of 16

![]()

Early Work and Icons

The first hint of Flavin's interest in fluorescent light is found in his 1961 verse form that reads:

flourescent

poles

shimmer

shiver

movie

out

dim

monuments

of

on

and

off

fine art.

That same year he began work on his icons series, in which incandescent and fluorescent bulbs are fastened to shallow, boxlike square constructions made from various materials such as wood, Formica, or Masonite. icon Five (Coran'south Broadway Flesh) is 1 of the largest and brightest of the icons, with twenty-viii incandescent "candle" bulbs lining the perimeter of the primal foursquare. By using the term "icon" to describe these early low-cal constructions, Flavin evokes the gold-ground religious icons of Byzantine art. But the term "icon" is used ironically, and hints at the artist's ambiguity toward his Catholic upbringing; icon V lacks the reverence of a sacred object, and instead projects a kitschlike quality, not merely in the use of the cheap incandescent bulbs, but also in the reference to the gaudy lights of Broadway.

Dan Flavin, icon V (Coran's Broadway Flesh), 1962, oil on common cold gesso on Masonite, porcelain receptacles, pull chains, and clear incandescent "candle" bulbs, 41 v/8 x 41 five/viii x ix vii/8 in. (105.nine x 105.9 x 25.one cm), Individual collection, New York Photo: Bill Jacobson, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Guild (ARS), New York

three of 16

Early on Work and Icons

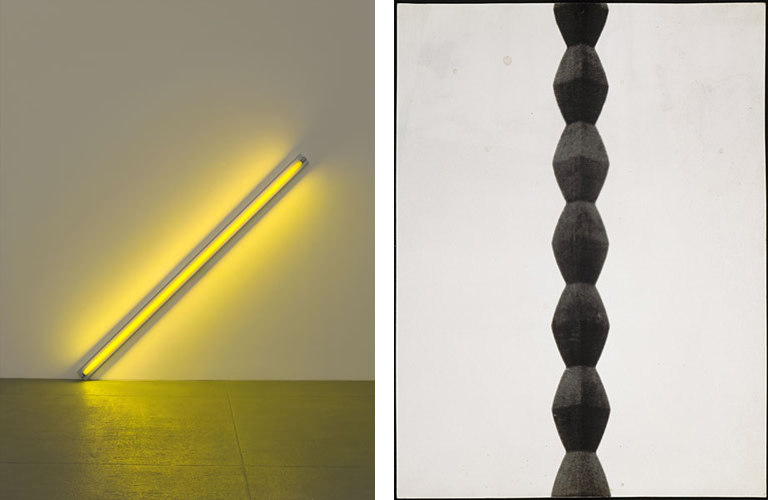

Flavin's breakthrough with fluorescent light was the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi). In this seminal work—the artist's first to apply fluorescent light alone—Flavin eliminated the square box of the icons, and instead positioned a single, unadorned xanthous fluorescent light at a 45-caste bending against a gallery wall. Struck by the effect, Flavin alleged the "gold" tube his "diagonal of personal ecstasy." He went on to draw that,

The radiant tube and the shadow bandage by its supporting pan seemed ironic enough to concur lonely. There was literally no need to etch this system definitively; information technology seemed to sustain itself directly, dynamically, dramatically in my workroom wall—a buoyant and insistent gaseous image which, through brilliance, somewhat betrayed its physical presence into approximate invisibility.

By declaring that a fluorescent light tube could stand on its own as a work of fine art, Flavin boldly yet just challenged the history of art, in particular the discipline's theoretical separation of art and everyday life. The critique follows in the philosophical footsteps of Marcel Duchamp, whose "readymades" of the early twentieth century consisted of ordinary, utilitarian objects (such every bit a wheel bicycle, bottle drying rack, or urinal) that Duchamp isolated from their functional context and placed within the environment of a piece of work of art. In and then doing, Duchamp deemed an object to be art past virtue of selection alone.

(left) Dan Flavin, the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), 1963, yellow fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) long on the diagonal, Dia Art Foundation Photograph: Baton Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York

(correct) Marcel Duchamp, 1887-1968, Fountain 1917, replica 1964, porcelain, unconfirmed, 36 x 48 ten 61 cm, Tate Gallery, London Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery, 1999, Photo: Tate Gallery, London, Art Resources, NY

4 of sixteen

Early on Work and Icons

Fifty-fifty every bit Flavin worked confronting the grain of fine art historical tradition, he also embraced it. The parenthetical dedication of the diagonal to Constantin Brancusi indicates his sentimental attachment to the modern Romanian sculptor. Indeed, Flavin non only dedicated the work to Brancusi, but straight compared his lone tube to Brancusi'due south famous "countless column," in which he stacked repeating wedge-shaped metal forms. Every bit Flavin explained, "Both structures had a uniform simple visual nature, but they were intended to exceed their obvious visible limitations of length and their credible lack of complication."

(left) Dan Flavin, the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), 1963, yellowish fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) long on the diagonal, Dia Fine art Foundation Photograph: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Club (ARS), New York

(right) Constantin Brancusi, Romanian, 1876-1957, Endless Cavalcade at Targu Jiu, 1938, Gelatin-silver impress, 15 5/viii ten 11 three/4 in. (39.8 x 29.vii cm), Musée national d'art moderne, Eye Georges Pompidou, Paris, Photo: Philippe Migeat, Courtesy Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Fine art Resource, NY

5 of 16

Early Piece of work and Icons

Another seminal early work is the nominal three (to William of Ockham), in which the creative person positioned half-dozen, eight-foot daylight fluorescent tubes vertically in a 1-ii-three progression spaced evenly beyond a gallery wall. The radical simplicity of his medium and the presentation of the fluorescent tubes in a basic progression encouraged viewers to perceive even slight differences. This involvement in and so-called seriality was of import non only for Flavin, but besides for many of his contemporaries. Flavin dedicated the work to the medieval nominalist philosopher William of Ockham (c. 1285-?1349), famous for his dictum known equally "Ockham's Razor": "Entities should non be multiplied unnecessarily." That is, the simple answer is the improve one. Hither Flavin reduces the "entities" of his fine art to the simple visual vocabulary of pure fluorescent light.

Dan Flavin, the nominal three (to William of Ockham), 1963, absurd white fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, Dia Art Foundation, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Club (ARS), New York

6 of 16

Minimalism and Abstraction

Flavin'south fluorescent lights grew out of the traditions of post–World War Ii American art. In the 1950s, brainchild became the dominant mode of creative expression, particularly in New York, which was rapidly establishing itself as an international art upper-case letter. The abstract expressionists, including such artists equally Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Clyfford Even so, produced nonobjective works that have a painterly quality to them: brushstrokes are visible, paint is immune to baste and puddle, and the artists' energy and movement are manifest, sometimes aggressively and then. Not all abstract, post-war painting favored the loose brushwork of gestural abstraction. Other abstract painters of this period, including Barnett Newman and Marking Rothko, painted large colour fields that are ofttimes described in spiritual terms. These painters were of enormous significance for Flavin; for example, there is a parallel between Rothko's luminous paintings with their glowing, hovering forms and the radiating colored lights of Flavin's work.

Dan Flavin, the diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), 1963, xanthous fluorescent light, viii ft. (244 cm) long on the diagonal, Dia Art Foundation Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York

vii of 16

Minimalism and Abstraction

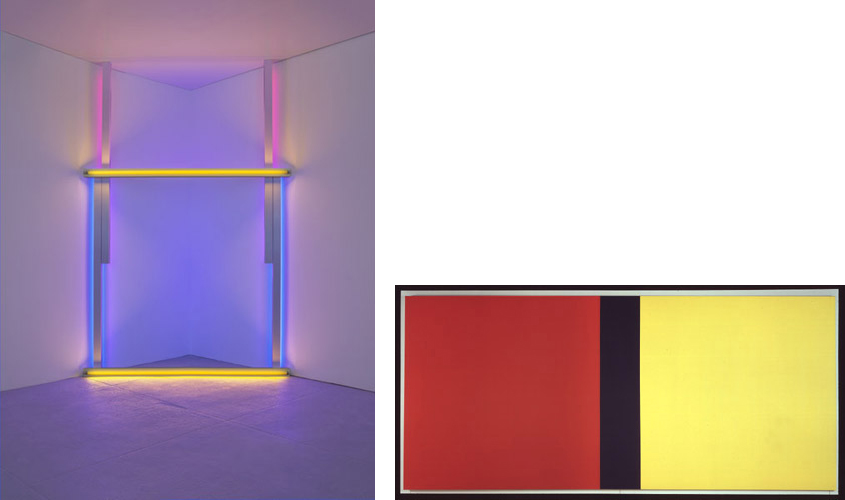

The thin, rigid lines of Flavin's fluorescent tubes that articulate an otherwise blank gallery wall also relate to the paintings of Barnett Newman, in which a narrow band of pigment—a "nada"—cuts vertically across a apartment field of contrasting colour. Flavin'southward deep regard for Newman is evident in several of his works, such every bit untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his simple problem, reddish, yellow, and bluish) whose title straight references some of Newman'south final paintings. While Newman'due south "zips" were praised for the way in which they established a new kind of pictorial space, Flavin went even further: His fluorescent lights really drain into the ambient space surrounding the fixture itself; the work of art, therefore, consists not merely of the fluorescent tubes, but also of the space they illuminate.

Newman was not just influential for Flavin, but his paintings were more broadly a precursor to minimalism, the move to which Flavin'southward art is oft ascribed (although the artist himself never approved of the term). The minimalists drew on post-war tendencies in abstraction, and developed a cool, rational aesthetic, expressed through the use of industrial materials, the erasure of the creative person's hand from the object, and the implementation of neutral, geometric forms. Along with Flavin, leading minimalists included Flavin's close friend Donald Judd, also equally other contemporaries such as Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre. The minimalists created objects that defied conventions of both painting and sculpture, a quality that distinguishes Flavin's fluorescent light constructions. Like sculpture, the lights are three-dimensional objects, nonetheless, like painting, they are often mounted flat confronting the gallery wall and involve the juxtaposition and mixing of colors.

(left) Dan Flavin, untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his simple problem, ruby, yellowish, and blueish), 1970, yellow, blue, and cherry fluorescent calorie-free superlative variable, 8 ft. (244 cm) wide across a corner, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Souvenir of the Barnett & Annalee Newman Foundation, in honor of Annalee G. Newman, and the Nancy Lee and Perry Bass Fund, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 2004.twoscore.1

(right) Barnett Newman, American, 1905-1970, Who'due south Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue IV, 1969-1970, acrylic on canvas, 108 x 239 in. (274 x 603 cm), Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin - Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie und Freunde der Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Photo: Joerg P. Anders, Courtesy Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz / Fine art Resources, NY, Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Club (ARS) New York

eight of sixteen

Hardware

Beginning in 1963, Flavin adopted commercially bachelor fluorescent lite every bit the primary medium for his art. Notably, he preferred standardized, utilitarian fluorescent calorie-free to custom-designed, showy neon. He bars himself to a limited palette (red, blue, greenish, pinkish, yellow, ultraviolet, and iv different whites) and course (straight two-, four-, half-dozen-, and eight-pes tubes, and, beginning in 1972, circles). Inside this restricted visual vocabulary he began a decades-long investigation into the behavior of lite.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his uncomplicated problem, red, yellow, and blue), 1970, xanthous, blue, and red fluorescent light summit variable, 8 ft. (244 cm) broad across a corner, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Souvenir of the Barnett & Annalee Newman Foundation, in honor of Annalee G. Newman, and the Nancy Lee and Perry Bass Fund, Photograph: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. 2004.40.1

ix of xvi

Hardware

Fluorescent light is produced by filling a drinking glass tube with a mixture of mercury vapor and argon gases. When electrified, the gases emit an ultraviolet radiations that causes the phosphorescent compounds that glaze the inside of the sealed glass tube to glow. Different phosphors radiate at different wavelengths, thereby producing the multiple colors. Because colored lite behaves differently than paint, Flavin's works ofttimes defy the expectations of viewers, who are frequently surprised and amused by the discovery of the properties of calorie-free. For case, mixing colors beyond the spectrum in paint renders pigment black; blending the colors of the light spectrum results, instead, in white light. This effect is beautifully illustrated in untitled (to Henri Matisse) in which pink, xanthous, blue, and green lights mix to produce an ambient white light. The piece of work is dedicated to Henri Matisse, the radical colorist whom Flavin admired.

(left) Dan Flavin, untitled (to Henri Matisse), 1964, pink, yellow, blueish, and green fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, Private collection, New York, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York

(correct) Henri Matisse, Open up Window, Collioure, 1905, oil on canvas, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.seven

10 of 16

Hardware

Primary colors too vary betwixt pigment and light. For pigments the primaries are red, yellow, and blue, whereas for light they are red, blueish, and green. (Dark-green mixed with ruddy makes yellow light). Flavin acknowledged this difference in greens crossing greens (to Piet Mondrian who lacked green), coyly dedicating a greenish low-cal work to Mondrian—the Dutch modernist famous for his chief color palette. This piece of work by Flavin also demonstrates another intriguing property of light: Green is the most brilliant fluorescent low-cal, and its intensity can be so strong that information technology nearly appears white. In contrast, fluorescent red is subdued. Because no mixture of phosphors can make a true red, the inside of the tube must be tinted, which in turn blocks the amount of emitted light. Thus, while cherry-red pigment is bold, red light, such as that seen in monument iv for those who have been killed in ambush (to P.Thou. who reminded me about expiry), 1966, is muted. Here, then, the red suggests violence and mortality, still the overall tone is subdued and elegiac rather than menacing.

(top left) Dan Flavin, greens crossing greens (to Piet Mondrian who lacked green), 1966, greenish fluorescent light, first section: 4 ft. (122 cm) loftier, twenty ft. (610 cm) wide, second section: 2 ft. (61 cm) loftier, 22 ft. (670 cm) broad, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Panza Collection, 1991 © Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York

(lesser left) Dan Flavin, monument 4 for those who accept been killed in deadfall (to P.Yard. who reminded me about death), 1966, red fluorescent lite, eight ft. (244 cm) wide, 8 ft. (244 cm) deep, Dia Art Foundation, Photo: Cathy Carver © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

(right) Piet Mondrian, Tableau No. Four; Lozenge Composition with Red, Gray, Blueish, Yellow, and Blackness, c. 1924/1925, oil on canvass, Gift of Herbert and Nannette Rothschild, 1971.51.1

11 of 16

"monuments"

Flavin direct approached the genre of the monument in his large serial, "monuments" for V. Tatlin, named for the creative person Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953). Tatlin was influential in post-1917 Russia, where he sought to apply his art to uphold the utopian ethics of the revolution. Flavin was especially struck by Tatlin'southward famous Monument to the Third International (1919-1920)—a project for a colossal, tilted iron tower surrounded past two spirals, containing rotating geometric glass halls. Never congenital, Tatlin's monument became a symbol for ambitious yet unrealized utopian dreams.

Flavin's "monuments" for V. Tatlin think their namesake's merging of art and technology and too speak to the Russian revolutionary's call for "real materials in existent space." As Flavin noted, "monument vii in cool white fluorescent light memorializes Vladimir Tatlin, the neat revolutionary, who dreamed of fine art as science. It stands, a vibrantly aspiring order, in lieu of his last glider, which never left the ground." Flavin's "monument" serial is deliberately ironic, even so, for Flavin's fine art is exceptionally "low tech," rejecting technological advances in favor of ordinary hardware. Flavin'south designation of the series as "monuments" (which he ever used in quotations) is equally paradoxical, for the impermanence of the fluorescent lights (the bulbs volition eventually burn out and demand replacing) counters the traditions of monuments and memorials as eternal reminders.

(left) Dan Flavin, "monument" 1 for V. Tatlin, 1964, cool white fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, Dia Fine art Foundation, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Guild (ARS), New York

(correct) Vladimir Tatlin, Monument to the Third Interntaional, 1920, wood, cardboard, wire, metal, and oil newspaper approx. 16 ft. (500 cm) loftier Courtesy Anatolii Strigalev

12 of 16

Light, Space, and Compages

Although Flavin'due south primeval fluorescent works were installed on the walls similar paintings, early on he began to explore the full space of the room, exploiting the disregarded margins. In 1964, at Flavin's outset solo exhibition at the Dark-green Gallery in New York, for example, the creative person hung a chief pic at the edge of the gallery wall, adjacent to a doorway. In occupying the edge, where wall meets empty space, Flavin abandoned the conventional space of fine art and allowed the art object to address the interior in a new way. With an ironic twist, Flavin constructed the fluorescent lights equally a rectangle surrounding a void, mimicking the shape of a pic frame and mocking the rigid traditions of art.

Dan Flavin, a principal picture, 1964, aureate, pinkish and red, red fluorescent light, 2 ft. (61 cm) high, 4 ft. (122 cm) wide, Hermes Trust, U.K.; Courtesy of Francesco Pellizzi, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

13 of 16

Light, Space, and Compages

In that same exhibition, the artist mounted pink out of a corner (to Jasper Johns). Placing this single, eight-foot pink fluorescent tube in the corner, literally illuminated what is, by convention, a darkened area of the installation space. Invigorating "dead space" with calorie-free became a powerful technique of the creative person, every bit seen in the subtle tones of untitled (to the "innovator" of Wheeling Peachblow). The palette of this light construction takes its cue from the hues present in Wheeling Peachblow glass, a nineteenth-century glass (largely manufactured in Wheeling, Westward Virginia) with deep coral to luminous xanthous coloration.

(left) Dan Flavin, pink out of corner (to Jasper Johns), 1963, pink fluorescent calorie-free, 8 ft. (244 cm) loftier, Collection Stephen Flavin, Photograph: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Gild (ARS), New York

(right) Dan Flavin, untitled (to the "innovator" of Wheeling Peachblow), 1966-1968, daylight, yellow, and pink fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) square across a corner, Photo: Billy Jim, New York © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Club (ARS), New York

14 of 16

Lite, Space, and Architecture

Flavin more thoroughly integrated his fluorescent calorie-free constructions with the surrounding compages in his so-chosen "corridor" pieces, in which a series of parallel fluorescent tubes extend across the width of a hallway, thereby blocking admission and forcing visitors to discover an alternative pathway. In untitled (to Jan and Ron Greenberg), a corridor is obstructed past bars of lite—green on one side, yellow on the other. A small-scale open up space between the last fluorescent tube and the wall permits a glimpse of the reverse color so that the main color is tinged by the effects of the light spilling in from the back.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to Jan and Ron Greenberg), 1972-1973, yellow and green fluorescent calorie-free, 8 ft. (244 cm) high, in corridor measuring 8 ft. (244 cm) high and 8 ft. (244 cm) broad, length variable, Dia Art Foundation, Photo: Florian Holzerr, Munich

15 of sixteen

Light, Space, and Architecture

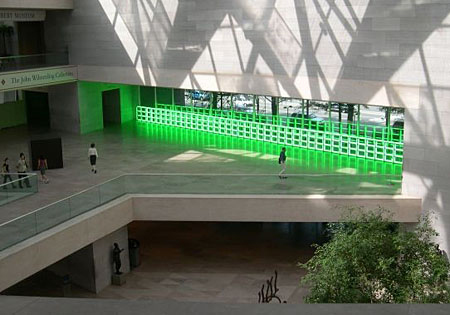

The construction untitled (to y'all, Heiner, with admiration and amore) embodies what fellow minimalist Donald Judd described as Flavin'due south "interior articulation" of a space. Extending some 120 feet, the installation of this "light-green barrier" at the National Gallery of Art fills and redefines the space of the mezzanine terrace past imbuing the mezzanine with a glowing light-green hue, impeding visitors' movement as they are forced to navigate around the monumental work and heightening their perception of the architecture.

Large-scale works became a focus of Flavin'south belatedly career, with site-specific lights commissioned for such diverse locations as Frank Lloyd Wright'due south spiral rotunda at the Guggenheim Museum, a converted nineteenth-century rail station in Berlin (now the Museum für Gegenwart), a converted church in Bridgehampton, New York (established in 1983 as the Dan Flavin Fine art Found), and a church in Milan, the last completed posthumously. While the scale had increased, the hardware, artful preoccupations, and ironic humor that Flavin demonstrated in his earliest calorie-free experiments were still evident. Dedicating virtually his entire career to the artistic possibilities of fluorescent low-cal, Flavin concentrated his efforts in a way rarely seen in the history of art. Restricting his materials was not a limitation, simply an enabler; he exploited subtle differences and establish depth, meaning, and beauty in what others overlooked.

Written past Lynn Kellmanson Matheny, Exhibition Programs, National Gallery of Art

Dan Flavin, untitled (to you lot, Heiner, with admiration and affection), 1973, green fluorescent light modular units, each 4 ft. (122 cm) broad, length variable, Collection Stephen Flavin © Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Guild (ARS), New York

sixteen of 16

carpenterupecent47.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nga.gov/features/slideshows/dan-flavin-a-retrospective.html

0 Response to "What Material Does Dan Flavin Use to Make Art?"

Post a Comment